TRADEMARK BOARD PUNCTURES TIRE COMPANY’S COUNTERCLAIMS

Based on an earlier registration for WARRIOR (Stylized), the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) granted a petition to cancel a registration for the mark ROAD WARRIOR and denied the respondent’s counterclaims of laches and abandonment. Double Coin Holdings, Ltd. v. Tru Development, Cancellation No. 92063808 (October 1, 2019) [precedential].

Double Coin Holdings, Ltd. (DC) owns a registration for WARRIOR (Stylized) as used for “casings for pneumatic tires; inner tubes for pneumatic tires; inner tubes for bicycles; tire flaps; vehicle wheel tires; automobile tires; tires for vehicle wheels; cycle tires; solid tires for vehicle wheels,” in International Class 12. DC obtained the registration in November 2007. Tru Development (Tru) registered its mark ROAD WARRIOR in September 2015 based on a claimed first-use date of January 2015. The registration covered “tires” in International Class 12.

DC filed its petition to cancel the ROAD WARRIOR registration on May 25, 2016. The petition alleged the priority of DC’s mark and a likelihood of confusion between the parties’ marks. Tru denied those allegations and asserted the counterclaims of laches, alleging that DC had waited too long to file its petition, and abandonment, alleging that DC had either explicitly abandoned use of WARRIOR (Stylized) or discontinued use of the mark with the intent not to resume use.

Given the dates relevant to the two registrations, the TTAB had little difficulty in finding that DC had priority in its mark. And given the similarity between the marks and the goods that the marks identify, the TTAB also found that, under the key factors set forth In re E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 476 F.2d 1357 (CCPA 1973), the ROAD WARRIOR mark was likely to cause confusion with the mark WARRIOR (Stylized). In reaching that conclusion the TTAB said that “ROAD” is highly suggestive of Tru’s goods and that “if a junior user takes the entire mark of another and adds a generic, descriptive or highly suggestive term, it is generally not sufficient to avoid confusion.” The TTAB’s findings with respect to priority and likelihood of confusion meant DC was entitled to have Tru’s registration cancelled under Section 2(d) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(d), unless Tru could prevail on at least one of its counterclaims.

With respect to Tru’s laches counterclaim, the TTAB said that the date of Tru’s ROAD WARRIOR registration, September 1, 2015, was the date on which the laches period began. DC filed its petition on May 25, 2016—only eight months later—and Tru did not cite a case in which such a short period was found to be unreasonable delay. Thus, the TTAB said, the period in question was insufficient “to be considered undue or unreasonable delay for laches to apply.”

Turning to the counterclaim of abandonment, the TTAB set forth the definition of abandonment due to nonuse of a mark:

"use that has been discontinued with an intent not to resume such use. Intent not to resume may be inferred from circumstances. Nonuse for 3 consecutive years shall be prima facie evidence of abandonment. ‘Use’ of a mark means the bona fide use of such mark made in the ordinary course of trade, and not made merely to reserve a right in a mark” (citing Section 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1127).

The TTAB added that “[a]ccording to the statutory language and legislative history, ‘nonuse’ of a mark for abandonment purposes means ‘no bona fide use of the mark made in the ordinary course of trade,’ and this is to be interpreted with flexibility to encompass a variety of commercial uses” (citing Lewis Silkin LLP v. Firebrand LLC, 129 USPQ2d 1015, 1018 (TTAB 2018)).

Because of high tariffs imposed in January 2015 on tires imported from China, DC’s U.S. distributor stopped selling DC’s tires in the United States after April 16, 2015. DC announced that the tariffs were the reason it had stopped exporting tires to the United States but did not say that it would never resume such exports. In an industry-standard approach to avoiding high tariffs, DC subsequently decided to build a tire factory outside China—in this case, Thailand.

The tariffs were lowered in March 2017, and DC resumed exporting tires to the United States in January 2018, with its U.S. distributor making the first sale of such tires on April 3, 2018. In light of the facts, the TTAB said that because Tru “did not definitively show that [DC] ceased use of the WARRIOR mark in commerce for at least 3 consecutive years, the burden of demonstrating [DC’s] abandonment remain[ed] on Tru” (citing P.A.B. Produits et Appareils de Beaute v. Satinine Societa in Nome Collettivo di S.A.e. Usellini, 570 F.2d 328, 332-33 (CCPA 1978) (“abandonment being in the nature of a forfeiture, must be strictly proved”)).

Tru also argued that DC had abandoned its mark WARRIOR (Stylized) by changing, from 2015 to 2018, the appearance of the mark from the form shown in DC’s registration to a somewhat different stylized form. The TTAB dismissed that argument by noting that “Tru never raised the abandonment by material alteration allegation in its counterclaim, nor in any amendment thereto during the course of the proceedings. Having not been pled, Tru cannot move forward at trial on this counterclaim” (citing Kohler Co. v. Baldwin Hardware Corp., 82 USPQ2d 1100, 1103 n.3 (TTAB 2007) (unpleaded allegations will not be heard)). After finding for DC on both of Tru’s counterclaims, the TTAB granted DC’s petition to cancel Tru’s registration for ROAD WARRIOR.

TITLE OF SINGLE WORK NOT REGISTERABLE AS TRADEMARK

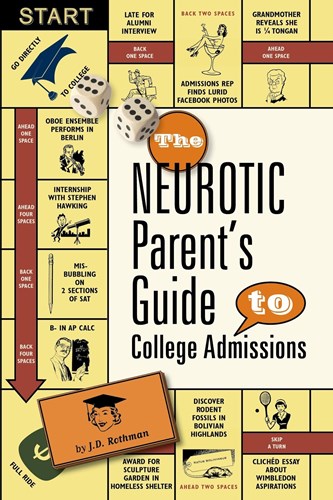

The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office affirmed a refusal to register THE NEUROTIC PARENT’S GUIDE on the grounds that it was the title of a single work, not a mark for a series of works. In re Rothman, Serial No. 85945757 (September 10, 2019) [not precedential].

Applicant Judith Rothman applied to register THE NEUROTIC PARENT for “publications, including books on the subjects of colleges and college admissions,” in International Class 16. In the first Office Action issued in connection with the application, the Examining Attorney advised Rothman that her application might be denied because her specimen of use, a book, seemed to indicate that the mark was the title of a single work and as such did not function as a trademark to indicate the source of Rothman’s goods. In response Rothman stated that she had used THE NEUROTIC PARENT with a blog since March 2008 and had posted hundreds of entries on the blog. In addition, she amended her identification of goods to “publications, namely, publications on the subjects of colleges and college admissions.”

The Examining Attorney issued a second Office Action stating that Rothman had to amend the identification of goods to specify the type of publication that would bear the applied-for mark. The Examining Attorney also stated that because a series is not established when only the format of the work is changed, Rothman had to submit evidence that THE NEUROTIC PARENT was used on at least two different creative works. In response Rothman amended her identification of goods to “publications, namely, books on the subjects of colleges and college admissions” and requested reconsideration of the Office Action. The Examining Attorney approved the application for publication, and a Notice of Allowance subsequently issued.

After taking five extensions of six months each, Rothman filed a Statement of Use and a specimen of use that consisted of a photograph of three identical books titled THE NEUROTIC PARENT’S GUIDE. The Examining Attorney issued a third Office Action, noting that the applied-for mark was THE NEUROTIC PARENT and that, based on the specimen, the mark was used only as the title of a specific book, not as a mark for a series of books. Rothman then amended her application to show the mark as THE NEUROTIC PARENT’S GUIDE and claimed that her blog was a second creative work. The Examining Attorney accepted the amendment but maintained the refusal to register the mark on the grounds that it was used only with a single work. Rothman appealed the refusal.

The TTAB began its analysis by noting that “[t]he title of a single creative work, such as a book, is not considered a trademark, and is therefore [unregisterable]” (citing Sections 1, 2, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1051, 1052, and 1127; In re Cooper, 254 F.2d 611, 117 USPQ 396, 400 (CCPA 1958)). The TTAB noted that this principle has long been settled, pointing to two cases more than a hundred years old: In re Page Co., 47 App. D.C. 195 (D.C. Cir. 1917), and Black v. Ehrich, 44 F. 793, 794 (C.C.S.D.N.Y. 1891) (Encyclopedia Britannica name not protected by trademark; “[n]either the author nor proprietor of a literary work has any property in its name”).

The Cooper court explained the reason for this rule:

There is a compelling reason why the name or title of a book of the literary sort cannot be a trademark. The protection accorded the property right in a trademark is not limited in time and endures for as long as the trademark is used. A book, once published, is protected against copying only if it is the subject of a valid copyright registration and then only until the registration expires, so eventually all books fall into the public domain. The right to copy which the law contemplates includes the right to call the copy by the only name it has and the title cannot be withheld on any theory of trademark right therein. (117 USPQ at 400)

In contrast, the TTAB said, “the name for a series of works is [registerable] because it functions as a trademark (citing Cooper as quoted In re Scholastic Inc., 23 USPQ2d 1774, 1776-77 (TTAB 1992) (holding that “THE MAGIC SCHOOL BUS, as used on books, would be recognized as a trademark identifying a series of children’s books emanating from applicant”)).

The TTAB disagreed with the Examining Attorney’s position that works in a series must be in the same medium and that therefore Rothman’s book and blog could not constitute a series. The TTAB cited In re Polar Music International AB, 714 F.2d 1567 (Fed. Cir. 1983), in which the Federal Circuit found trademark usage of the name of the musical group ABBA, noting that “[e]very ‘ABBA’ album and single and tape has the word ‘ABBA’ on it in addition to its title.” Id. at 1572 (emphasis added).

Nevertheless, the TTAB said, Rothman was not seeking to register a common characteristic in the titles of her book and blog; she was seeking to register the title of the book. But “[t]he book title, as shown in [Rothman’s] specimen of use, does not prominently display the words THE NEUROTIC PARENT in a way that would make a commercial impression separate and apart from THE NEUROTIC PARENT’S GUIDE. That is the opposite of the holding in the THE MAGIC SCHOOL BUS case.”

The TTAB noted that Rothman’s book and blog appeared to have a common theme—advising parents about colleges and college admissions—but said that “we are left to guess about their differences, if any. [Rothman] has provided representative entries from her blog, but none of the content from her book” (footnote omitted). Rothman’s counsel asserted that Rothman’s book contains material not published on her blog, but the TTAB said that “[a]ttorney argument is no substitute for evidence” (citing Enzo Biochem Inc. v. Gen-Probe Inc., 424 F.3d 1276, 1284 (Fed. Cir. 2005), as quoted in Zheng Cai v. Diamond Hong, Inc., 901 F.3d 1367, 1371 (Fed Cir. 2018)). “In the absence of record evidence differentiating the contents of the two works,” the TTAB said, “we are unable to conclude that they constitute a series.”

In conclusion, the TTAB said, although “it is possible for titles of creative works in different media to form a series, the evidence of record in this case does not show that the applied-for mark is the title of the claimed series, or that the content of the creative works differs sufficiently to create a series.” Accordingly, the TTAB affirmed the refusal to register the mark.